Crackers, Fog, and an H-Boat Called Ali Baba

Two sixteen-year-old boys crossing the Baltic in a 24-foot H-Boat — and the friendship I didn’t know I’d spend a lifetime remembering.

A short detour from the heavier pieces this week. I’ve shared a story from my teens — a sailing trip across the Baltic that became one of those memories that refuses to fade. Friendship, fog, hunger, and the kind of freedom you only understand decades later.

Weekend reading, if you’re in the mood.

FOREWORD

Sverre and I had known each other for as long as memory has a shape.

Seven years old, Svalnäs Skolan, Djursholm—matching school bags, scraped knees, and the sort of quiet confidence that comes from growing up in the same comfortable neighbourhood, learning the same tricks, and wanting roughly the same things.

We weren’t identical, but we were aligned.

He was better with his hands; I was faster on skis.

He played instruments; I didn’t.

He was brilliant at school; I got on by indifference and selected effort.

He usually got the girl; I usually didn’t complain about it.

But when it came to the things that mattered—boats, mopeds, music, speed, the sea—we were equals.

People didn’t think of us separately.

We came as a pair.

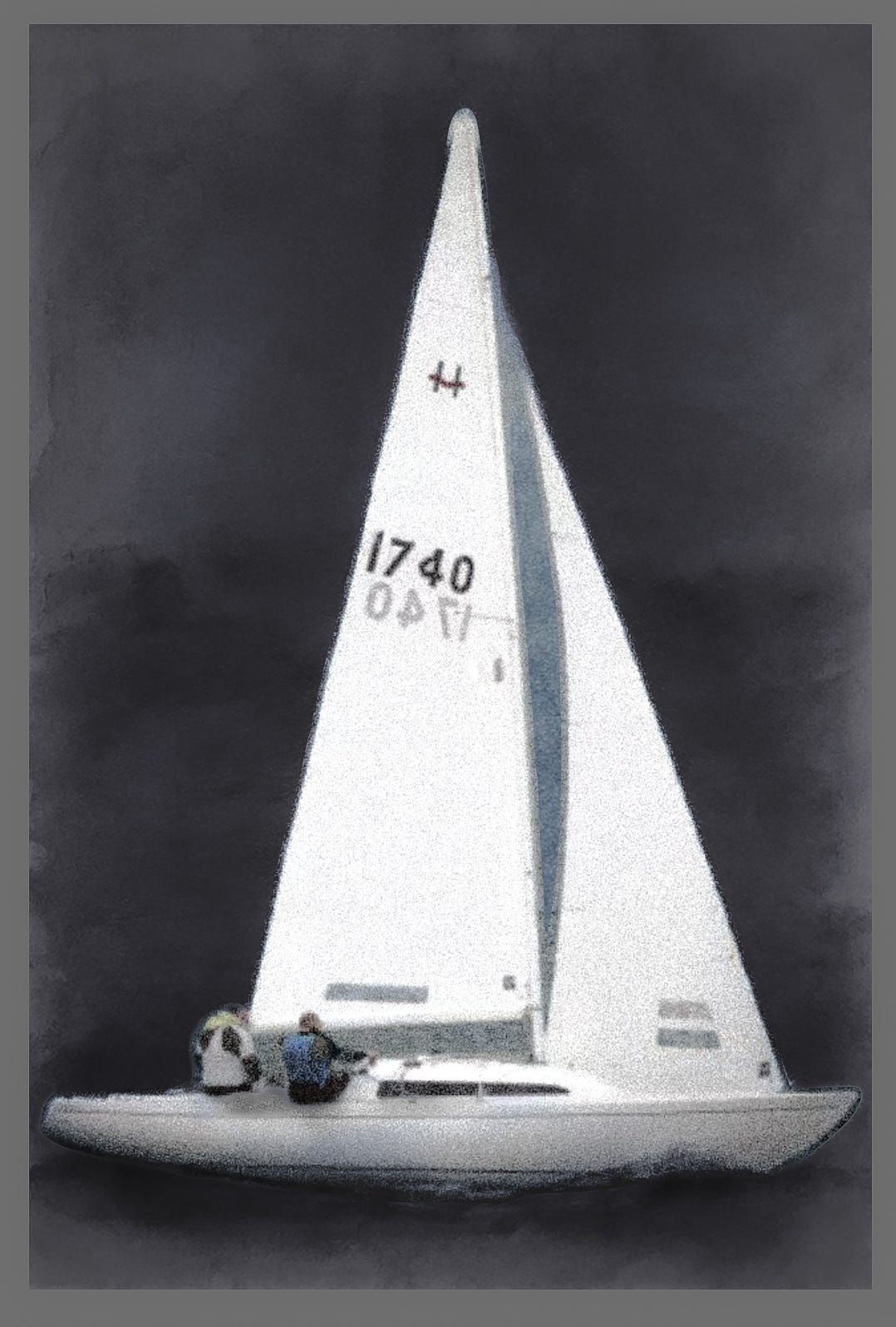

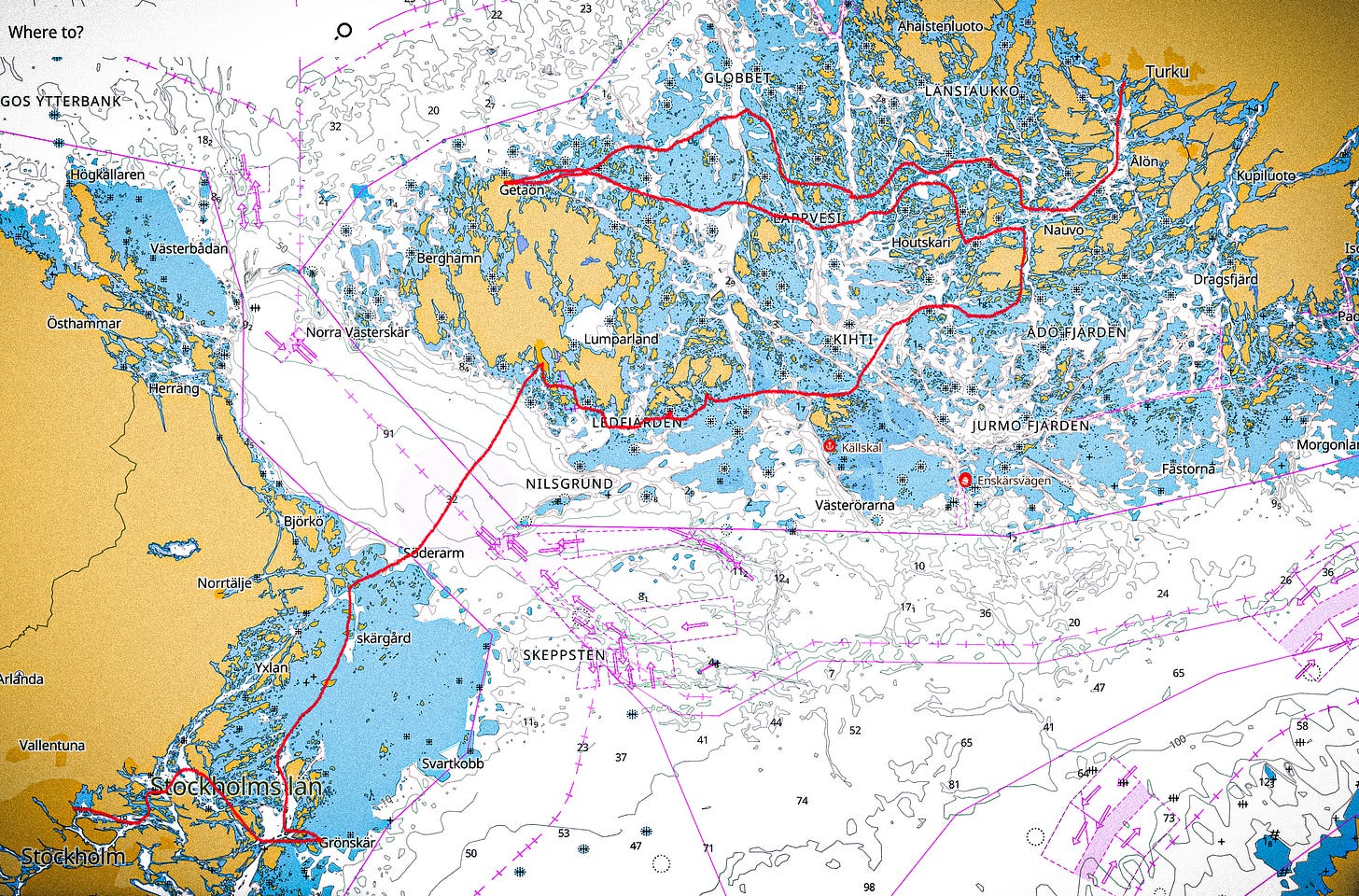

And so, in the summer of 1976, as sixteen-year-old boys who believed themselves halfway to adulthood, we set off on a voyage through the Swedish and Finnish archipelagos in a 24-foot H-Boat named Ali Baba.

No radio.

No engine.

No adult.

Just wind, charts, a dubious compass, and the kind of overconfident logic unique to boys who haven’t yet discovered what fear really is.

This is the story of that trip—of hunger and salt, of improvisation and laughter, of small victories and bigger mistakes, and of the kind of friendship that feels effortless at sixteen and impossible to recreate later in life.

It remains one of my best sailing memories.

And one of my clearest memories of Sverre.

—Eric

PROLOGUE — The Compass That Didn’t Work

At sixteen, time doesn’t behave like time.

The days stretch, the nights hesitate, and the sun in the archipelago hangs on the horizon like it’s not entirely sure it wants to leave.

We left Sandhamn with full confidence and almost no food.

That felt normal.

There’d been the customary detour past the KSSS clubhouse—because even though we were only sixteen, I’d been a member since birth, and the place held a strange pull over any Djursholm boy with a boat and an ego.

It was also the unofficial summer marketplace of teenage ambition: sun-bleached hair, deck shoes, and the vague hope that a girl you’d been too shy to talk to all year might say hello to you on the dock.

We stayed long enough to pretend we weren’t there just for that.

Then we cast off.

Ali Baba was a Finnish-designed H-Boat—long, narrow, and built for racing. No engine, no electrics, no luxuries.

Just sails, a stubborn hull, and two boys who thought “navigation” meant pointing the boat where you felt land might be.

Our instruments were modest:

one Silva compass that only worked if held flatter than a pancake

a battered marine monocular with a bearing ring that disliked being breathed on

a handful of Swedish and Finnish charts

and eyes trained to recognise ferries at absurd distances

What we lacked in tools, we compensated for with teenage certainty.

Which is to say: we guessed.

A lot.

The fog rolled in halfway across Ålands Hav, swallowing horizon, depth, and any remaining sense of direction.

The compass sulked.

The sea-birds vanished.

The sun gave up entirely.

But ferries we trusted.

Ferries had jobs—serious, adult, reliable jobs.

Spot one heading vaguely east and you could follow it like a pilgrim trailing a prophet.

And so we did.

Watching silhouettes materialise and dissolve in the fog, trimming sails, listening to the water for hints.

Slowly, improbably, the markers of Mariehamn emerged.

We were triumphant.

Slightly damp, slightly hungry, slightly feral—but triumphant.

Then we discovered the town was closed.

Entirely.

Not a sound, not a shop, not a rumour of life.

We found a man walking a dog and asked for the time.

“Eight,” he said.

“In the morning?”

“No. Evening.”

“What day is it?”

“Sunday.”

Right.

Of course it was.

We hadn’t known what day it was for at least a week.

One in seven chance—and we’d landed squarely on the quietest one.

But we didn’t care.

We’d crossed the open sea in a racing dinghy without an engine or a clock.

We’d found the harbour we were aiming for.

We hadn’t hit anything important.

For sixteen-year-old boys, this counted as spectacular success.

Chapter 1 — No Engine, No Watch, No Problem

Leaving Sandhamn always feels more dramatic than it probably deserves.

Something about that harbour—the creaking docks, the varnished classics, the men in red trousers, the girls in white sweaters—creates the illusion that every departure is a major voyage. Even if you’re only heading for the next island, it looks like the start of something epic.

For us, it was epic.

We were sixteen, sailing to Mariehamn in an H-Boat with no engine and no common sense. That counts.

Of course, we’d first done the required ceremonial stop at the KSSS clubhouse. I’d been a member since childhood, which meant we could stroll in like entitled heirs despite looking like we’d slept in a boathouse. It was also where teenage boys went to pretend they weren’t trying to get noticed.

We loitered in that particular Swedish teenage way—acting deeply casual while hoping something thrilling might happen. Nothing did. But tradition requires the attempt.

Eventually we tore ourselves away, cast off, and pointed Ali Baba toward open water.

She was a beautiful little beast—24 feet of Finnish pedigree, long and lean, light as a dancer, completely impractical for cruising, and wholly unreliable as a home.

Perfect for us.

Her equipment list was admirable in its minimalism:

No engine.

No radio.

No watch.

No navigation electronics whatsoever.

A Silva compass that worked only when held flatter than Sweden’s east coast.

Charts so worn they looked like they’d spent a season in the Viking Age.

One monocular whose bearing compass functioned only if you didn’t inhale.

But we also had something better than instruments:

confidence.

Confidence bordering on idiocy, but confidence nonetheless.

The crossing started well.

Light westerly, steady speed, swell manageable.

We took turns pretending to consult the compass, then admitted reality and watched the birds instead. Seabirds know everything. If they’re heading east, that’s probably where Åland is. Good enough.

Then the fog arrived.

Not dramatically—just a slow greying of the world. The horizon dissolved, sound grew thick, and the boat became the only solid object left in creation. We trimmed the sails, stayed silent, and switched to our real navigation method.

Ferries.

We knew the big Finland–Sweden ferries by silhouette, schedule, and temperament. If one appeared through the fog heading east, we followed it like stray dogs. Ferries don’t get lost. We respected that.

The fog didn’t lift, but it thinned enough near the end for shapes to appear—trees, markers, the low shadows of the outer approaches. We eased in under sail, found the channel, and glided into the stillness of Mariehamn.

We were spent but proud.

And starving.

We expected a lively harbour—restaurants, girls, music, the smell of grilling meat. We found silence. Absolute, uncanny silence. Even the gulls seemed to be on break.

We spotted a man walking his dog and asked the time.

“Eight,” he said.

“In the morning?”

“Evening.”

“What day?”

“Sunday.”

Right.

Naturally.

Of course we’d crossed half the Baltic to arrive on the only day Mariehamn becomes a monastery.

But it didn’t matter.

We’d arrived.

Under sail.

On target.

Without an engine, a watch, or a single correct navigational tool.

For two sixteen-year-old boys, it felt like winning the Whitbread.

We tied up, stretched our legs, and laughed for no real reason except that sixteen-year-olds sometimes do. We had no food worth mentioning and no plan for the morning.

Which meant we were exactly where we wanted to be.

Chapter 2 — Skiftet, Spray, and the Stolen Tin of Sardines

By the time we left Mariehamn, the fog of the crossing had lifted but the fog in our planning hadn’t. We had food in the same way a magician has a rabbit: theoretically, somewhere, if you squint. Most of what we were living on could be summarised as “crackers and optimism.”

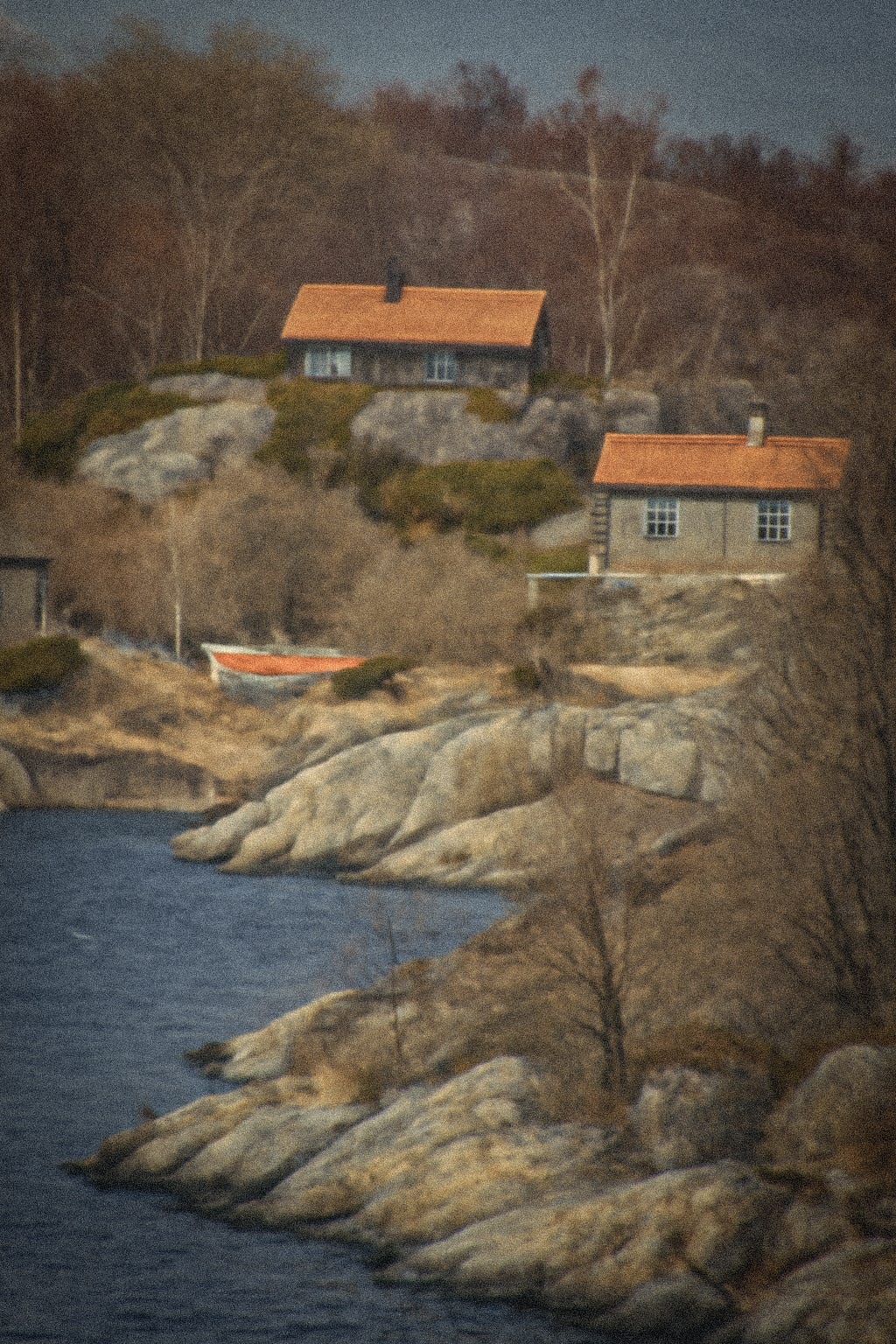

We pointed Ali Baba vaguely south-east, through the scattered edges of the Åland archipelago. This was the feral part — the granite backbone of the sea. The kind of islands the Vikings might have rowed past with a grimace and said, “Not today.” But at sixteen, barren rock felt like an upgrade. It looked real. Ancient. Honest. Like the sea had stripped away anything unnecessary.

Our goal — in the loosest sense — was Skateboard Island.

A place we’d named ourselves because the granite slabs were shaped like a skate park. Naturally, we had a skateboard aboard.

No engine.

No radio.

No idea what day it was.

But a skateboard.

Civilisation.

But before Skateboard Island came Sommarö — the last harbour before crossing Skiftet, the open water between Åland and Finland. We arrived in what can only be described as a gale worthy of Norwegian storytelling exaggeration. The harbour was rammed with cautious adults. Triple-rafted boats. Fenders squealing. Lines stretched like violin strings. The sensible sailors were hiding.

We arrived under full sail.

Not out of bravado — out of necessity. When you don’t have an engine, you don’t do “careful approaches.” You do managed crash landings. And Ali Baba, bless her narrow little bones, tracked like she’d been designed for chaos. We rounded the entrance, dumped the sails at the last rational second, and coasted silently into a gap beside a 40-footer whose crew looked at us as if we’d arrived from space.

We nodded at them like this was perfectly normal.

Inside Sommarö’s little shop — “shop” in the generous sense — we gathered provisions with the kind of laser focus that only true hunger produces. Which items were paid for and which simply… transitioned into our pockets is lost to history. Hunger scrambles ethics. And we were polite enough to apologise to the shopkeeper for “not finding what we needed,” which he graciously accepted without chasing us out with a broom.

Back at the quay, a few adults — warm, well-fed, admirably clueless about teenage logic — asked if we were really going to cross Skiftet in this weather.

We found the question puzzling.

This was a sailing harbour.

We had a sail.

The wind was blowing.

What else was supposed to happen?

Once we cleared the harbour, the sea wasted no time making its opinion known. Waves slapped us like we owed them money. Spray hit the cockpit like thrown gravel. Sverre turned a colour that doesn’t appear on charts.

“Bucket?” he croaked.

I handed him the galley pot, wedged a cushion under him, and lashed him into the forward corner. He accepted his fate like a condemned philosopher and vomited with stoic dignity for the next two hours.

For my part, I was in heaven.

Ali Baba was alive.

Surfing down swells, leaping forward, shaking off every crest like a terrier too proud to admit it’s small.

Just before dusk, Skateboard Island rose out of the horizon like an old friend who never asks questions because it already knows the answers. Bare granite. Sloping slabs. No trees. No shelter. Perfect.

We tied up in the last of the light, emptied our soaked pockets onto warm rock, and ate whatever passed for dinner: sardines, crisp bread, something beige that might once have been meat.

We were wet, exhausted, and blissfully alive.

Sverre eventually sat up.

He smiled.

Or grimaced. Hard to say.

But the worst was behind us, and we had a whole island of stone and stupidity to play with the next day.

Chapter 3 — The Days Between

The thing about adventure — real adventure — is that most of it isn’t adventure at all. It’s drift. It’s silence. It’s two boys killing time in ways that feel urgent in the moment and faintly ridiculous decades later.

After Skateboard Island, we slid into the long, delicious stretch of nothingness that only a pair of half-feral sixteen-year-olds can fully appreciate. No timetable, no adults, no instructions — and more importantly, no interruptions. The world shrank to a cockpit, some rocks, and whatever we could invent to fill the hours.

We fished.

A lot.

Not the charming, Instagram-friendly kind of fishing. The real stuff — trolling half-asleep through narrow straits, holding rods with the slack determination of boys who don’t actually want fish so much as the illusion of competence. If we caught something, excellent. If we didn’t, we blamed the fish for being lazy.

Fishing made us feel industrious, which at sixteen is the gateway drug to self-respect.

We also had an air rifle aboard.

A detail which today sounds borderline criminal, but in 1970s Scandinavia barely registered as notable. Nobody cared. The coastline was essentially a vast granite playground supervised by no one. If anyone had tried to oversee us, the archipelago itself would’ve coughed politely and said, “Let the boys be idiots; it’s tradition.”

So we shot at things.

Not people — that would’ve made the news.

But fish? Logs? The occasional overly arrogant seagull? Entirely fair game. We were, in our own minds, supplementing the food supply. In reality, we were supplementing the noise.

When we weren’t shooting at lunch, we swam. Surprising distances. Ridiculous dives. Utterly pointless laps between rocks. We swam because the sun was warm, the granite was hotter, and because proving you could leap off a stupidly high boulder without screaming counted as character development at sixteen.

The only watchers were gulls that seemed faintly embarrassed for us.

And then — the games.

My God, the games.

We played damp-backgammon, soggy-Yatzy, and what became known as the Island Edge Challenge, which had two rules:

Walk around the entire perimeter of whatever island we’d moored to.

Do it on the very edge. Not near it. On it.

The result was always the same: one of us fell in. The losing penalty was unclear, because falling in was half the pleasure.

The second great invention was The Boat Race — a competition with stakes so unnecessarily high that one would think we were designing yachts for the Americas Cup. The rules:

Three hours to build a sailboat from whatever the island provided.

No tools except a knife.

Hull, mast, keel, sail — all from twigs, bark, leaves, stolen driftwood, perhaps divine intervention.

Launch in a tidal pool.

First boat across wins eternal, fleeting glory.

We argued about these boats as if committees in Geneva were waiting for our verdict.

They were pathetic little contraptions, of course — listing, flapping, occasionally sinking with dignified resignation. But they mattered because we made them matter, and at sixteen that’s the closest thing to meaning you ever need.

Those days between were made of small things inflated to full size:

the slap of water against rock, the whisper of wind through pine needles, the smell of salt drying on bare shoulders.

We were tired.

A little hungry.

Sunburned in stupid patterns.

And freer than we had any right to be.

The strange, beautiful part is that we didn’t know it.

Not then.

Freedom at sixteen isn’t recognised — it’s inhaled, ignored, spent like pocket money. Only later does it reappear in memory, glowing with the slow, golden light of things you didn’t have the sense to appreciate.

But that’s youth.

It isn’t meant to be understood while you’re in it.

Only after the fact, when the map is behind you, does the shape of the journey make sense.

Chapter 4 — Edith’s Island

After a week of salt, sunburn, and nutrition that could only be described as “aspirational,” the idea of Nagu began to feel less like a waypoint and more like a pilgrimage. Not because of the town itself, but because of Edith — the one dependable source of civilisation in our adolescent universe.

Edith wasn’t a relative.

She wasn’t even a family friend in the traditional sense.

She was an institution.

The kind of woman the archipelago produces once a generation: carved from wind, birch bark, and pure granite willpower. You didn’t talk over Edith. You didn’t argue with her. You simply arrived, were assessed, and were either accepted or quietly dismissed back to the sea.

We’d been to her island before — with our parents, back when responsible adults pretended we were impressionable. But this time it was just us: two feral sixteen-year-olds sailing in on a tiny, engine-less racing boat, looking like we’d been living under a tarpaulin and smelled like the inside of a wetsuit.

We walked up from the jetty with that peculiar mix of humility and confidence that boys develop when they’re too hungry to be proud. Edith emerged from somewhere — she always emerged, never “arrived” — glanced at us, took in the state of our clothes, our hair, perhaps our souls, and simply said:

“You came alone?”

Not shocked.

Not impressed.

Just verifying the terms of engagement.

We nodded.

She nodded.

Contract established.

We were in.

And so began two days of voluntary indentured labour.

We hauled nets heavy enough to change theology.

We carried wood from one mysterious shed to another even more mysterious shed.

We moved crates filled with objects so enigmatic we didn’t dare ask what they were — the archipelago version of classified material.

We were probably more hindrance than help, but Edith never complained. She wasn’t built for complaint. She was built for continuity — the quiet, immovable authority of someone whose life runs on tides and seasons, not excuses.

And then there was the food.

After weeks of eating like sailors on the losing side of history, the sight of her long wooden table bordered on religious revelation. Smoked fish. Proper potatoes. Dense bread. Milk from an actual jug, not a paper packet resembling hospital supplies. Everything tasted like the island itself — earth, salt, smoke, and a kind of no-nonsense comfort that teenagers can’t name but recognise instantly.

No chatter.

No small talk.

Just the clink of cutlery and the kind of silence that says: This is how things are done here.

We slept like the dead.

Woke with a sense of borrowed belonging.

For forty-eight hours, we were neither children nor intruders — just temporary islanders, folded into Edith’s personal weather system.

On the second morning, we packed up reluctantly. Edith met us at the shoreline with a canvas bag filled with smoked perch, hard cheese, and cured meat — enough provisions to make us feel like kings for the next stretch of sea.

She handed it over as if it were nothing.

We accepted it as if it were everything.

No ceremony.

No thanks beyond a nod.

Edith wasn’t a woman you thanked.

She was a woman you respected.

And then we pushed off — sails catching before we’d even cleared the jetty, Ali Baba gliding back into the channels with a belly finally full enough to keep the world wide and possible again.

Edith shrank behind us, becoming not a figure on a dock but a silhouette against a landscape — one of those rare people who leave an imprint larger than the moment.

We didn’t know it then, of course.

But she was one of the last adults in our lives who belonged wholeheartedly to an older world — the slow, ancient, uncompromised kind. The world we were sailing out of without realising it.

Chapter 5 — The Northern Edge

Leaving Edith’s island felt a bit like re-entering normal physics after spending two days in a quieter, older gravitational field. We’d slept in real beds, eaten food with density and flavour, and been treated — in Edith’s uniquely austere way — as if we were worth feeding. That kind of thing spoils boys more than money ever could.

With our bellies full and our clothing marginally less offensive, we pointed Ali Baba north. The aim wasn’t precise — nothing ever was — but I wanted to reach the very top of Åland again. Geta Djupvik. The northern edge. A place that had always felt like it was half in this world and half leaning into something colder and more ancient.

The sailing was easy at first. The sun lingered over the horizon in that reluctant northern way, as if it had forgotten how to set. The wind was gentle. The water calm. For a while, we drifted through a version of the archipelago that could lull any fool into underestimating it — wide channels, low islands, smooth granite slopes that looked like they’d been designed specifically to invite barefoot wandering.

Then the geography shifted.

Almost imperceptibly at first — a harsher angle here, a darker line of rock there — but within a few hours, the whole coastline had changed its temperament. The islands grew taller. Steeper. Less welcoming. The kind of granite that doesn’t want to be climbed but allows it if you insist.

You could feel the water change, too.

Colder.

Heavier.

A different density entirely.

This was the Gulf of Bothnia breathing southwards — salt thinning, depth increasing, the sea taking itself far more seriously. The sort of water that doesn’t care about teenage boys in a racing dinghy with no engine and a heroic overestimation of their own competence.

We spent a few days roaming there, tucked into lonely coves that felt like the corners of an old myth. No kiosks. No cottages. No cheery boaters making coffee in their cockpits. Just the wind hissing through pine needles, the slap of water against stone, and the occasional bird that looked at us as if to say, “What are you doing here?”

It wasn’t the dramatic part of the trip.

But it might have been the best part.

We climbed cliffs barefoot until our heels complained.

We scrambled over boulders because boys can’t resist climbing something taller than themselves.

We scattered the silence with laughter and pointless debates and half-serious existential thoughts that felt profound at sixteen.

There was no goal.

No urgency.

Just the elemental sense of being suspended at the far edge of the map — where the world feels slightly larger than you remembered and your place in it slightly smaller.

One morning, I stood on a cliff looking northward, where the archipelago loosened into open water. Nothing but horizon. The line where Sweden, Finland, and boyhood all blurred.

And I thought — not dramatically, not epically, just quietly:

This is as far as we go.

Not a limit, not a failure — just a recognition.

This was the top edge of our summer.

Beyond this point, the story wasn’t expanding anymore.

It was bending toward home.

I didn’t tell Sverre why I wanted to turn back.

He didn’t ask.

Friendships at sixteen don’t need explanations. They run on instinct, not conversation.

So we pulled up the anchor, sheeted in the sails, and let Ali Baba pivot away from the northern edge — that thin borderland between land, sea, and the end of something we were too young to understand we were already losing.

Chapter 6 — East Toward Åbo/Turku

By the time we left the northern edge behind, the trip had taken on that odd elastic quality that long summer adventures develop: we felt both completely timeless and vaguely aware that the clock — the real one, the mainland one — was waiting somewhere up ahead with a raised eyebrow.

And sure enough, reality had scheduled a rendezvous for us:

My father was going to meet us in Åbo.

This meant two things.

First, we needed to arrive in roughly the same week he expected us.

Second, he would be bringing Eva — his new girlfriend.

Eva was 28, Estonian, athletic enough to look aerodynamic even while standing still, and formerly his secretary. It was the kind of midlife plot twist that practically writes its own punchlines. Sverre and I found it hilarious. My father did not.

But before he could be exasperated by us, we had to actually get to Åbo — which required a piece of information we hadn’t had in weeks:

What day is it?

We didn’t have a watch.

I never wore one in summer.

When the sun barely sets, time becomes optional — like parents or money.

Still, we made a guess.

Four days? Maybe five?

Close enough.

So we turned southeast, away from the cold breath of the Gulf of Bothnia, and threaded Ali Baba through narrowing channels that felt like doorways back into civilisation. The shift was subtle but unmistakable: the islands grew greener, softer, less like Viking monuments and more like places where you might find a mailbox and a mildly disappointed homeowner.

After the wide spaces up north, it felt like moving from cathedral to corridor.

The water got busier too.

Yachts. Motorboats. Ferries.

People who clearly had schedules, responsibilities, and functioning wristwatches.

We, naturally, had none of those things.

Eventually we reached the wire ferries — squat little workhorses that get dragged across straits by underwater cables thick enough to anchor an ego. The rule was very clear:

Never sail too close behind one.

If your keel caught the wire, you had two options:

Tear the bottom off your boat.

Stop dead with the force of a cartoon anvil.

Neither appealed.

By this point, though, we were skilled in the art of alert teenage competence: a mode in which boys who can’t remember their own shoe size suddenly develop battlefield-grade situational awareness. We scanned the water like hawks. We listened for the slap of steel on the surface. We threaded between ferries, fishing boats, and holiday sailors with the easy arrogance of youth and the luck of fools.

On the final day, the wind grew lazy. The channels tightened. Boats moved in choreographed loops around markers and shoals. Everything felt busier — we were sailing into a world that had shape and rules again.

And we felt it —

that subtle unwinding of the spell.

The trip’s logic had shifted.

We weren’t exploring anymore.

We weren’t improvising or surviving or proving anything.

We were returning.

And there’s always something a little sad about that, even when you don’t recognise it at the time.

But sixteen-year-olds don’t do melancholy.

Not properly.

Not yet.

We just kept sailing — eating Edith’s cheese, dodging ferries, pretending we weren’t looking forward to a real bed even though we absolutely were — and let Åbo draw us in like the inevitable last chapter of a book we weren’t quite ready to finish.

Chapter 7 — Arrival

Åbo didn’t sneak up on us.

It presented itself.

After weeks of granite, wind, silence, and the mild nutritional neglect that only teenagers find acceptable, civilisation was almost overwhelming. The channels grew orderly. The boats were clean. People wore clothes that had clearly been washed on purpose. And then the Åbo Sailing Club appeared — white buildings, polished rails, a kind of maritime austerity that said: This is where grown-ups behave themselves.

It was, in short, not ready for us.

I’d been there before, with family, when adults acted like adults and children were supposed to follow suit. I knew the drill — the tone, the manners, the choreography of propriety. But arriving as two sun-battered sixteen-year-olds who’d crossed half the Baltic on crackers and delusion? That was a different kind of entrance.

Ali Baba, to her credit, looked immaculate.

Finnish pedigree.

Narrow, fast, elegant.

A boat that could bluff her way into any harbour.

Her crew… could not.

We tied up looking like survivors of a military experiment involving saltwater immersion and questionable laundry standards. Clothes faded into an off-grey rarely seen in nature. Hair stiff with sun and wind. Faces dried out to the colour of burnt driftwood.

We walked up the dock as if this was completely fine.

Inside, the sailing club’s hotel lobby exuded the calm, confident wealth of a place that assumes its guests arrive by Volvo rather than by boat at risk of sinking. Polished floors. Brass fittings. Staff in uniforms with epaulettes — epaulettes! — the international symbol for “Whatever you’re about to ask for, it will cost money.”

The concierge gave us a look usually reserved for people who’ve wandered in from the wilderness clutching a warning about an approaching storm.

He asked for the name of the boat.

“Ali Baba,” I said, with the serene confidence of someone who knows the boat looks far better than he does.

“And the names of the captain and crew?”

This was the moment his eyebrow ascended into the kind of arch that suggested he was revising his understanding of the natural order.

Two 16-year-old boys, salt-crusted, red-eyed, clothes several washes past redemption, standing in a hotel frequented by men named Rolf who talk about “port tack” over dessert.

But we were polite.

Djursholm boys always are.

We can do old-money etiquette on command, even while looking like shipwreck survivors.

Besides, the reservation was already made.

By my father.

Who, unbeknownst to him, had authorised an entirely different category of spending.

We were handed keys.

Not one room — two.

Each with a balcony.

A harbour view.

Linen sheets that felt like they’d been woven by angels.

A minibar stocked like the opening scene of a Bond film.

Within an hour, we had showered off 1976.

We were reborn.

And then there was the buffet.

A Finnish smörgåsbord is not a meal.

It is an event.

An assault.

A revelation.

When you’ve spent weeks living on kaviar tubes and crackers, stepping into a room with professionally cooked food feels like entering Valhalla. We ate like polite wolves. We drank beer with the supreme confidence of boys who looked just old enough to get away with it — and in a hotel full of sailors, nobody checked.

For two glorious days, we lived like kings.

Teenage kings, yes — but kings nevertheless.

And then my father arrived.

With Eva.

Eva was… spectacular.

Tall. Blonde. Lithe.

An Estonian volleyball player turned secretary turned post-divorce companion.

She moved like someone who could spike a ball through a brick wall.

Sverre was speechless.

I smirked just enough to be noticed.

“Something funny?” my father asked, in a tone that suggested the answer should be “No.”

“Not at all,” I said. “She seems… very committed to team sports.”

His expression darkened.

Which, of course, made it funnier.

And then the bill arrived.

My father — poor man — assumed we had checked in the night before.

In reality, we had checked in two nights earlier.

In that time, we had:

eaten enough buffet food to trouble an accountant

consumed beer at a rate suggesting impending adulthood

emptied both minibars

slept on sheets that should only be entrusted to clean people

and enjoyed the full luxury allocation intended for respectable sailors

His face — as he read the invoice — was a masterpiece of paternal horror.

Worth the entire trip.

We left the hotel like gentlemen.

Took a taxi to the airport — which at the time was smaller than most petrol stations. The loudspeaker crackled:

“The next flight to Stockholm will depart from Gate 1.”

There was, of course, only one gate.

And only one flight.

We boarded.

We sat down.

We looked out the window as Åbo shrank behind us.

And just like that, the summer ended.

Not with drama.

Not with triumph.

Not with any sense of finality at all.

Just two boys heading home — sunburnt, changed, quietly proud, blissfully unaware that they’d just lived through a story they’d spend the rest of their lives trying to explain.

A fantastic short story perfectly portraying a unique time and place when youth was free, the archipelago was unspoilt and sailing required true seamanship. This story might as well have been about Tom and Huckleberry.