Quantum Theory Without a Map

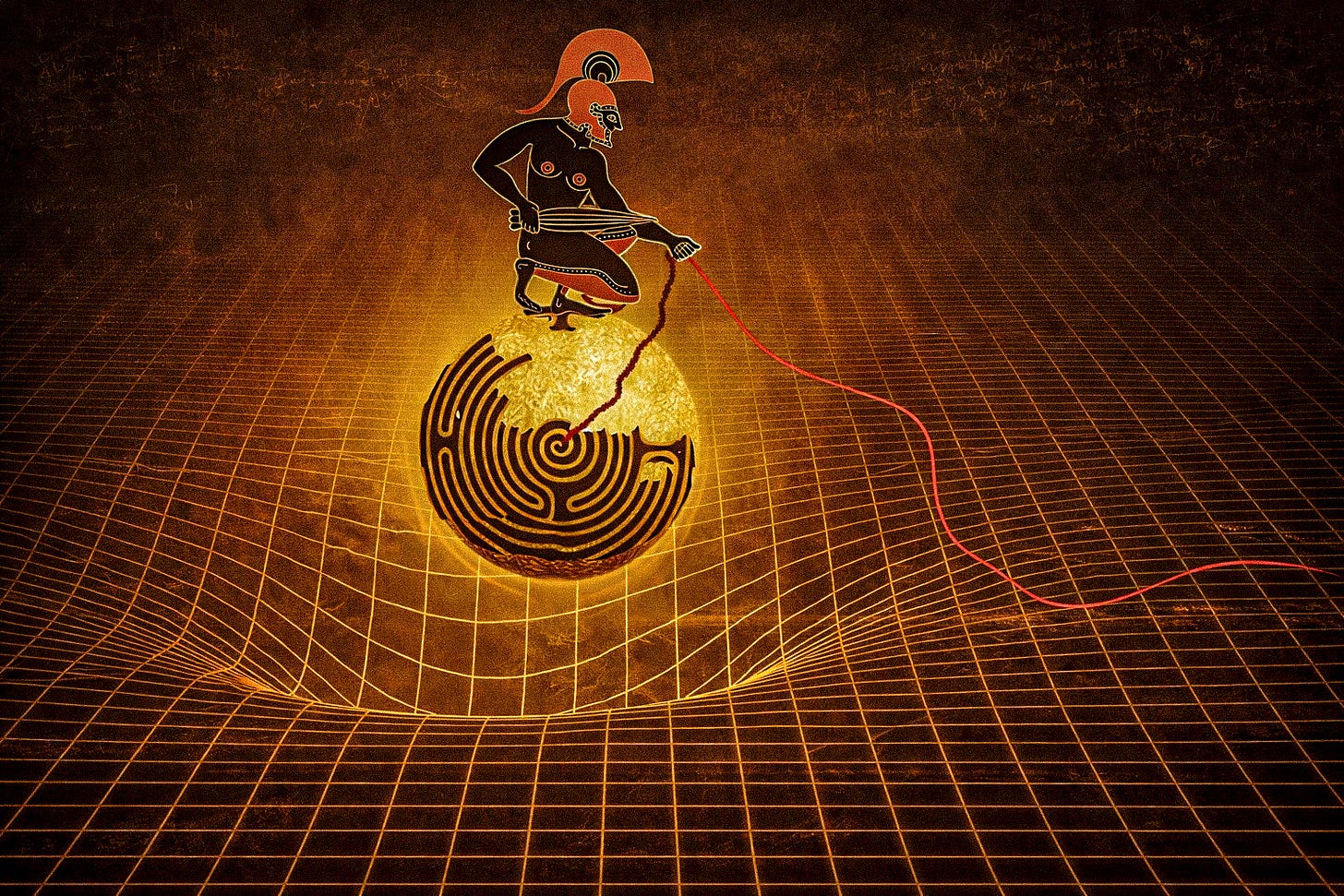

The Minotaur, the thread, and disciplined exploration at the edge of physics

1. Entering Without a Map

At the edge of physics, we are not seeking a final map of the labyrinth, but a thread that lets us explore without losing our way.

For more than a century, physics has lived with a peculiar asymmetry. We possess theories of extraordinary predictive power, capable of engineering technologies that shape modern life, yet we remain uncertain how to speak about what those theories say the world is. Quantum theory, in particular, works with an almost unsettling reliability, while resisting any single, stable account of its meaning.

This is not a crisis of competence, nor a failure of mathematics. It is a crisis of language — or, more precisely, a recognition that our existing language may no longer be adequate to the territory we have entered.

When Edward Witten remarks that we may not yet know the language in which quantum theory is written, he is not gesturing toward mysticism or retreat. He is stating a sober methodological fact: calculation has outpaced comprehension. We can move confidently within the structure, but we cannot yet describe the structure itself without borrowing metaphors that break under pressure.

In such a situation, insisting on a complete map becomes a liability. The more responsible posture is orientation rather than closure — knowing where one started, how far one has travelled, and how to return if necessary. Exploration must remain reversible. That is the function of the thread.

2. The Labyrinth We Inherited

Quantum theory did not arrive as a grand philosophical reimagining of reality. It entered physics almost reluctantly, as a working assumption introduced to repair a specific technical failure.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Max Planck proposed that energy exchange might occur in discrete packets — quanta — not because nature demanded it philosophically, but because the equations otherwise refused to cooperate. Quantisation was initially a constraint, a rule imposed to make calculation possible, not a claim about the fundamental structure of existence.

In retrospect, that modest assumption opened an entire domain. What followed was not merely a refinement of classical physics, but the gradual discovery that classical concepts — continuity, locality, objecthood, causality — could not survive intact. The mathematics flourished, but the accompanying language fractured. Particles behaved like waves in evolution and like particles in interaction, while being neither in any classical sense. Observation entered the formalism without a clear physical definition. Probability ceased to describe ignorance and became structural.

More than a century later, the situation is paradoxical but stable. Quantum theory predicts outcomes with astonishing precision, yet offers no consensus account of what is happening between those outcomes. We can build quantum computers, manipulate entanglement, and trust the formalism with increasing confidence — all while disagreeing fundamentally about what it means.

That persistence is not an embarrassment. It is a signal. When a theory remains operationally complete but conceptually unresolved for 125 years, the most economical explanation is not stubbornness or lack of imagination, but a mismatch between the depth of the structure and the language available to describe it.

The labyrinth, in other words, is real. It is internally consistent, mathematically rigorous, and navigable in practice — but resistant to global description. Treating this resistance as a defect misses the point. It may instead be a boundary marker, indicating where existing forms of explanation reach their limit.

At such boundaries, progress does not come from declaring victory or retreating to comfort. It comes from learning how to move without getting lost — and from remembering where one entered.

3. Knowing How Without Knowing Why

Quantum theory places us in an unusual position. We understand how to use it far better than we understand what it describes.

This is not a rhetorical complaint. It is a structural fact about the theory. Quantum mechanics allows us to calculate probabilities with astonishing accuracy, to manipulate entanglement, to engineer devices that rely on its most counterintuitive features — and yet it offers no single, agreed account of what is happening between those calculations and outcomes. The theory delivers results, not narrative.

Historically, this reverses the usual order of understanding. In classical physics, explanation preceded application: forces acted on objects, trajectories followed causes, and mathematics formalised an already intelligible picture. In quantum theory, the sequence is inverted. The formalism works first; meaning struggles to follow.

This inversion has consequences. It forces us to distinguish between two kinds of understanding that are often conflated: operational mastery and ontological clarity. We possess the former in abundance. The latter remains unsettled.

When we say that a quantum system exists in superposition, or that particles behave like waves in evolution and like particles in interaction, we are not describing physical processes in the classical sense. We are naming constraints on prediction. These statements tell us what the theory allows us to calculate, not what is literally taking place in space and time.

That distinction matters. Much of the unease surrounding quantum mechanics arises from treating calculational rules as incomplete stories about reality — and then demanding that they behave like stories. But quantum theory does not fail because it refuses narrative closure; it succeeds precisely because it does not require one.

At the same time, refusing to ask what the theory is saying about reality is not a neutral position. It merely postpones the problem. Over time, metaphors harden, provisional language becomes habitual, and scaffolding quietly turns into belief. The danger here is subtle: not that we speculate too freely, but that we forget which parts of our understanding are structural necessities and which are interpretive conveniences.

This is where orientation becomes essential. When a theory works without telling us what it is about, the task is not to force an explanation prematurely, nor to abandon inquiry altogether. The task is to move carefully, to keep track of where assumptions enter, and to preserve the ability to retrace our steps.

It is at this point — when knowledge is effective but meaning is unstable — that exploration becomes hazardous. Not because the terrain is irrational, but because it is internally consistent enough to lure us into thinking we have reached solid ground.

And it is here that an old image becomes useful.

4. The Minotaur

The greatest danger at the edge of physics is not ignorance. It is false certainty.

This is where the image of the labyrinth becomes useful — not as explanation, but as orientation. In the Greek myth, the labyrinth is not chaotic. It is structured, internally consistent, and navigable. The danger does not lie in confusion, but in losing the ability to return. The Minotaur is not the unknown; it is what happens when one mistake’s orientation for understanding.

Theseus does not enter the labyrinth armed with a map. No such map exists. He enters with a thread — a simple device that preserves reversibility. The thread does not explain the maze. It does not defeat it. It merely ensures that exploration does not become entrapment.

The Minotaur, in this metaphor, is not quantum strangeness. It is not superposition, entanglement, or uncertainty. These are features of the terrain. The Minotaur is something more familiar and more dangerous: the moment when provisional language hardens into belief, when metaphor begins to masquerade as ontology, when a calculational scaffold quietly turns into a picture of reality.

This danger is subtle precisely because it emerges from success. Quantum theory works so well that its working assumptions can feel foundational. Phrases intended as placeholders — wave, particle, collapse, measurement — begin to behave like nouns rather than constraints. Over time, what began as a way to calculate becomes something we think we understand.

At that point, the labyrinth has done its work. Not by confusing us, but by persuading us that we are standing on solid ground when we are not.

This is why restraint matters. When Edward Witten cautions that we may not yet speak the language in which quantum theory is written, he is not declining to explore the labyrinth. He is refusing to mistake familiarity for fluency. Mathematical discipline, in this context, is not conservatism; it is self-preservation.

By contrast, more adventurous thinkers — Roger Penrose, for example — have been willing to range further into the maze, proposing new structures, new connections, new explanatory bridges. This kind of exploration is not undisciplined; it is mathematically rigorous. But it carries a different risk: the further one moves from the thread, the harder it becomes to return.

Neither posture is wrong. Both are responses to the same terrain. The difference lies not in courage or intelligence, but in how much risk one is willing to accept in the absence of a shared language.

The lesson of the Minotaur is not that exploration should stop. It is that exploration must remain reversible. The danger is not asking what lies beneath quantum theory, spacetime, or causality. The danger is forgetting where the questions began — and losing the ability to distinguish what we know from how we navigate what we do not.

To survive the labyrinth, one does not need a final answer. One needs a way back.

5. Ariadne’s Thread

If the Minotaur represents the danger of false certainty, then the thread represents something far more modest — and far more valuable. It is not a solution. It is a discipline.

In the myth, the thread given by Ariadne does not reveal the structure of the labyrinth. It does not shorten the journey or point directly to the centre. Its only function is to preserve orientation — to ensure that every step forward remains connected to the place of entry. The thread is not knowledge; it is reversibility.

At the edge of physics, this distinction matters. When explanation falters and language strains, the task is not to replace mathematics with metaphor, nor to elevate imagery into belief. It is to maintain a stance that allows exploration without entrapment — a way of moving that remains accountable to where one started.

This is the role played here by a deliberately provisional picture: quantum theory, classical matter, and spacetime not as separate domains, but as interacting regimes of stability — with spacetime acting as a ceiling for quantum evolution until a deeper language explains how that ceiling itself emerges.

This image does not claim ontology. It does not assert what reality is. It simply marks relationships. Quantum fields give rise to stable excitations; stable excitations behave as particles and atoms; at larger scales, these collective structures curve spacetime and generate gravity. Nothing is sharply divided, and nothing is final. These are descriptive regimes, not stacked worlds.

Crucially, the image also has limits — and those limits are part of its usefulness. To treat spacetime as a ceiling is not to declare it fundamental. It is to acknowledge that, within current quantum theory, spacetime is assumed rather than explained. The picture holds just long enough to orient inquiry, and no longer. When it fails, it is meant to fail visibly.

That visibility is the safeguard. A thread that snaps unnoticed is worse than no thread at all.

This is why calibration matters. Exploration happens forward, but understanding happens backward. One moves into the labyrinth tentatively, then looks back to see which assumptions held, which metaphors stretched, and which quietly hardened into belief. The logbook must be updated continuously — not to declare right or wrong, but to maintain bearing.

Used this way, imagery becomes neither decoration nor dogma. It becomes a temporary scaffold — elastic, revisable, and openly incomplete. It allows movement without pretending arrival.

The purpose of the thread is not to defeat the labyrinth. It is to make exploration survivable while the language is still forming.

6. When the Walls Begin to Leak

Some discoveries do not add new rooms to the labyrinth. They make holes in its walls.

This is the role played by Stephen Hawking’s discovery of black-hole radiation. On its surface, Hawking radiation appears as a technical result — a subtle quantum effect arising near an event horizon. But its significance lies elsewhere. It reveals that horizons are not absolute, that black holes are not perfectly black, and that spacetime boundaries thought to be final may, under quantum scrutiny, be permeable.

Hawking radiation emerges precisely where two descriptive regimes collide. It requires quantum theory operating in the presence of curved spacetime — a situation in which spacetime can no longer function as a silent ceiling. The result is not a neat unification, but a tension: quantum effects appear to undermine the classical certainty of horizons, singularities, and finality.

This tension matters because singularities play a quiet but foundational role in modern physics. In general relativity, singularities mark the limits of description — the centres of black holes, the putative beginning of the universe. They are not objects so much as signals that the theory has been pushed beyond its domain of validity. Hawking radiation sharpens that signal. If information can escape, if black holes evaporate, if horizons soften, then the classical picture of a sealed singularity begins to look like an artefact of language rather than a feature of reality.

The implications extend outward. If singularities inside black holes are suspect, then cosmological singularities — including the one often associated with the Big Bang — must also be treated with caution. This does not invalidate cosmology, nor does it erase the well-supported picture of an early hot, dense universe. It does, however, weaken the idea that the universe began from a literal point where physics itself emerged fully formed.

Once again, the issue is not mathematical failure. The equations remain consistent. The issue is interpretive strain. Hawking radiation does not tell us what replaces the singularity; it tells us that the classical boundary is not final. The wall leaks, but the space beyond is not yet charted.

Within the scaffold developed so far, this is exactly where stress should appear. A theory that treats spacetime as a stable foundation works until spacetime itself must participate in quantum behaviour. When it does, the ceiling buckles. The result is not collapse, but ambiguity — a sign that the descriptive regime is being asked to do work it was never designed to perform.

This is why Hawking’s contribution is so unsettling and so important. It does not offer a new picture to replace the old one. It removes a false sense of closure. It forces us to admit that boundaries we relied on — horizons, singularities, beginnings — may be provisional constructs rather than final facts.

In the language of the labyrinth, Hawking did not confront the Minotaur. He revealed that some walls were thinner than we believed. And once walls can thin, the distinction between inside and outside, before and after, becomes less secure.

At that point, the thread matters more than ever.

7. Why the Question of Why Keeps Moving

One of the more unsettling features of modern physics is that the deepest questions rarely disappear. They migrate.

We explain the behaviour of particles in terms of fields. We explain fields in terms of symmetry and constraint. We explain symmetry in terms of mathematical structure. And then, inevitably, we ask why that structure holds — only to discover that the question has moved again, now pointing toward spacetime, information, or origin.

This is often described as frustration, or even failure. But it may be better understood as a signature of layered description. Each time a theory succeeds within its domain, it pushes the unanswered questions outward, toward the boundary where its language no longer applies.

In the earlier sections, quantum theory explained how interactions occur without explaining what entities ultimately are. General relativity explained gravity by geometrising spacetime, without explaining why spacetime has the structure it does. Hawking radiation then destabilised the very boundaries — horizons and singularities — that had allowed us to stop asking questions at all.

The result is not confusion, but displacement. The “why” does not vanish; it relocates.

This is where the labyrinth metaphor earns its keep. The labyrinth does not change as we walk through it, but our position within it does. What once appeared as a wall becomes a passage; what once looked like an end becomes a turn. The danger lies in mistaking any local clearing for the centre.

The Minotaur returns here — not as a monster lurking at the heart of reality, but as a reminder of a recurring temptation: to believe that the question has finally been answered because it has been temporarily quieted. Singularities once played that role. So did indivisible particles. So did absolute time. Each offered a place to stop.

Each, in time, proved to be provisional.

Seen this way, the persistence of “why” is not evidence that science has stalled, but that it is doing exactly what it has always done: advancing by replacing final answers with deeper questions. The discomfort comes from forgetting that this is normal — or from expecting that one particular generation should be the one to reach the centre.

Greek mythology is useful here precisely because it does not promise such resolution. The labyrinth has no privileged vantage point. The Minotaur is not slain by understanding the maze, but by surviving long enough to confront it — and even then, survival depends on remembering the way back.

For those of us watching from the outside — the “mortals”, as some put it — this perspective matters. It prevents awe from turning into mystification and humility from turning into resignation. It reminds us that not knowing why yet is not the same as not knowing where we are.

The thread does not silence the question. It allows us to keep asking it without pretending that the maze owes us an endpoint.

8. Discipline at the Edge

When explanation stalls and language frays, the solution is not to retreat into comfort or to speculate without restraint. It is to tighten practice.

This may sound counterintuitive. If the problem is that our concepts are inadequate, why insist on discipline? Because the absence of discipline is precisely what turns exploration into drift. At the edge of physics, method matters more, not less.

The distinction that becomes essential here is between disciplined exploration and aimless speculation. Disciplined exploration accepts uncertainty, but refuses to lose track of assumptions. It allows provisional images, but demands that they remain reversible. It tolerates ambiguity, but insists on calibration.

This is where returning to imagery is often misunderstood. To revisit imagery is not to abandon mathematics or regress to pre-scientific thinking. It is to recognise a recurring pattern in the history of science: when formal systems reach their limits, new understanding does not arrive as better equations alone, but as a reorganisation of the conceptual scaffolding beneath them.

Images precede language. Language precedes mathematics. This is not a romantic claim; it is a historical and cognitive one. Before calculus, there was geometry. Before spacetime metrics, there were thought experiments with clocks, trains, and falling observers. Before field equations, there were lines drawn in sand and iron filings on paper.

What makes this return productive rather than regressive is constraint. Imagery must be bounded by what is already known, anchored to successful formalism, and subjected to constant backward checks. The image is not there to explain the theory. It is there to track where explanation fails.

This is where the thread reasserts itself as method. Each advance into the labyrinth is accompanied by a deliberate act of looking back: Which assumptions entered unnoticed? Where did a metaphor begin to carry more weight than it should? At what point did convenience harden into belief?

Calibration is not an admission of weakness. It is the only way to move forward without accumulating hidden commitments. The logbook matters because memory is unreliable, and because success has a way of disguising its own scaffolding.

This practice is visible, in different forms, across the landscape of modern theoretical physics. Some insist on extreme mathematical constraint before taking even a tentative step. Others range further, testing structures at the edge of coherence. What distinguishes serious exploration from noise is not the distance travelled, but whether a clear path back remains.

In the language of the labyrinth, this is the difference between walking with a thread and wandering until orientation dissolves. The Minotaur is avoided not by timidity, but by method.

At this stage, the goal is not to unify quantum theory, spacetime, and gravity under a single banner. It is to remain capable of recognising when a new language begins to form — and to ensure that, when it does, we know which questions it was built to answer.

That is not a philosophical stance. It is a working discipline.

9. The Thread, Not the Map

At the edge of physics, the temptation is always the same: to demand a map.

Maps promise closure. They suggest that if only enough detail were filled in, the labyrinth would flatten into a diagram, the centre would reveal itself, and the journey would end. But this is not how foundational understanding has ever advanced. When maps appear too early, they freeze assumptions that should have remained provisional.

What has served science better, time and again, is something humbler: a thread.

A thread does not tell you where the centre is. It does not guarantee that there is a single centre at all. What it offers instead is continuity — a way to move forward without severing contact with what has already been learned. It preserves reversibility, accountability, and the ability to say, this is where we started; this is how far we have gone; this is where the picture began to strain.

This matters now because physics finds itself in an unusual position. Its most successful theories remain extraordinarily predictive, yet increasingly opaque. Quantum mechanics works without telling us what its entities are. General relativity explains gravity while refusing to explain spacetime itself. Attempts at deeper structure gesture toward new languages we do not yet speak fluently.

In such a moment, impatience is understandable — but dangerous. So is overconfidence. The right posture is neither conquest nor retreat, but careful exploration under constraint.

The Greek myth endures not because it explains the labyrinth, but because it respects its nature. There is no view from above. There is only motion, memory, and method. Survival depends less on bravery than on remembering how one arrived at each turn.

If this approach feels unsatisfying, that may be because it refuses to pretend that understanding is closer than it is. But it also avoids a more serious error: mistaking the absence of final answers for the absence of progress.

Progress, at this depth, looks like improved orientation. Clearer boundaries. Better calibration. Fewer hidden assumptions. A growing sensitivity to where language breaks down and where a new grammar might eventually form.

We are not yet ready to name that grammar. Perhaps we are not even ready to recognise it when it appears. But we can ensure that, when it does, we are not lost.

At the edge of physics, the task is not to slay the Minotaur, nor to redraw the maze from imagination alone. It is to keep hold of the thread — to explore far enough to matter, carefully enough to return, and honestly enough to know the difference.