THE KITCHEN SCALE

On the Measurable, the Immeasurable, and the Strange Human Habit of Trusting the Instrument Over the Experience

Introduction

(Part IV of the Cosmic Kitchen Series)

There comes a point in any exploration — physics, philosophy, baking, or simply being alive — when you realise you’ve spent a great deal of time describing the tools without ever stepping back to look at the kitchen they belong to.

The Cosmic Kitchen Series started with three humble utensils: the Teaspoon, the Whisk, and the Sieve.

Each captured something about the way consciousness and the universe behave — metaphors that made sense to me long before I could explain why.

But now feels like the moment to bring them all onto the same worktop and see what they reveal together. Because consciousness isn’t merely a teaspoon dipped into experience; it’s a teaspoon inside a cosmic mixture being whisked into turbulence and sifted into coherence long before we show up to notice anything.

These metaphors aren’t science. They’re simply the clearest way I can picture how reality feels.

Which brings us to the awkward bit: human measurement.

Our beloved habit of confusing “what we can measure” with “what is real.”

And that’s where the Kitchen Scale walks in — earnest, literal, and blissfully unaware of its own limitations. The perfect emblem of the human mistake: weighing the world with something that only measures the parts small enough to fit on the pan.

Before we get to the moral of the story, let’s set the scene.

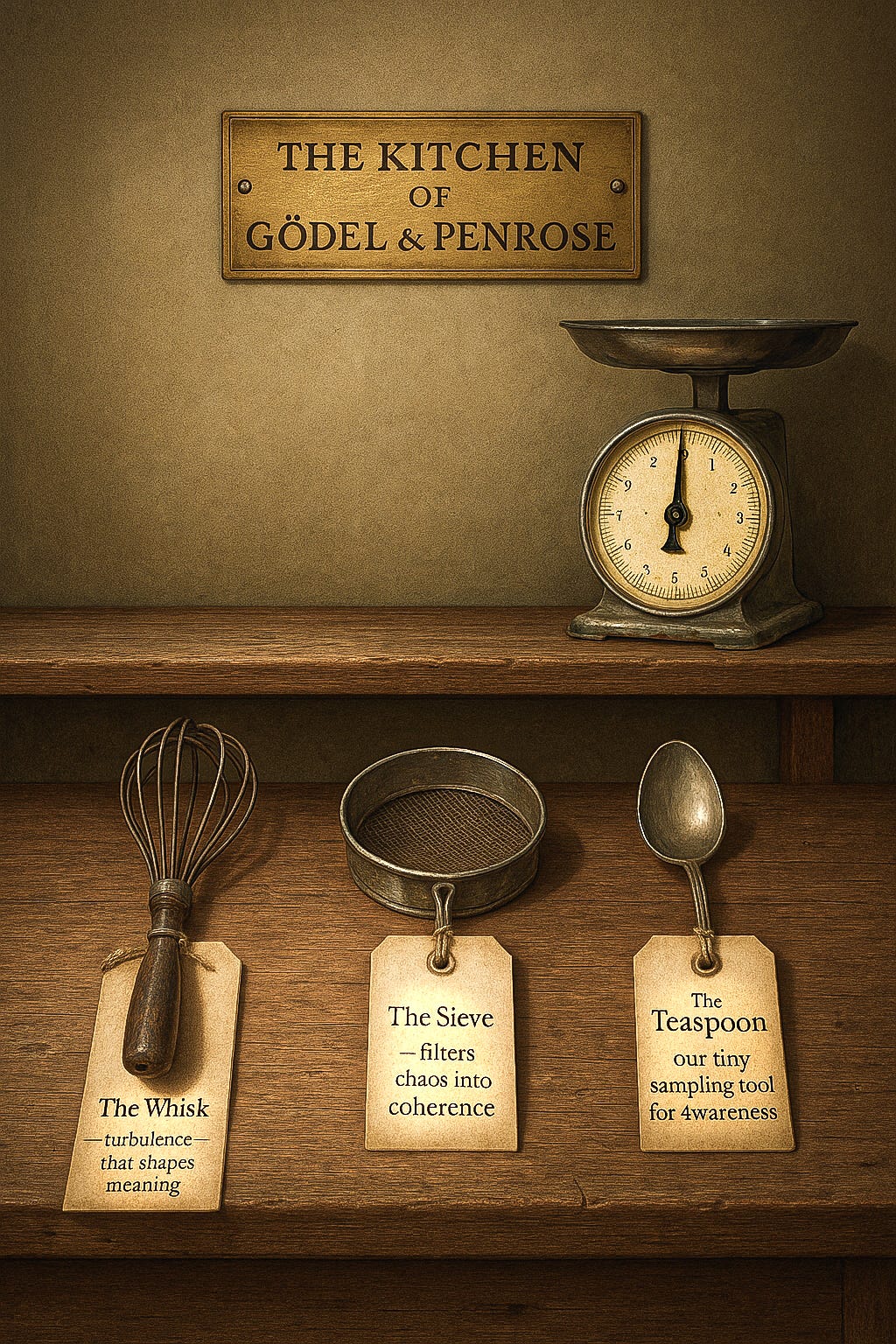

From the Kitchen of Gödel & Penrose

— where turbulence becomes meaning, chaos becomes coherence, and reality remains stubbornly unmeasurable

The Tools on the Worktop

On a wooden worktop lie three simple kitchen utensils, neatly arranged like the instruments of a craftsman:

The Whisk — turbulence that shapes meaning

The Sieve — filters chaos into coherence

The Teaspoon — our tiny sampling tool for awareness

These aren’t objects so much as cosmic behaviours:

chaos being stirred into pattern

pattern being sifted into structure

structure being tasted by human awareness in the smallest possible scoop

This is the machinery of the universe long before measurement enters the room.

And below the worktop — a little sheepishly — sits the Kitchen Scale.

A solid, old-fashioned mechanical thing.

Sturdy. Honest. Confident in all the wrong ways.

The perfect symbol for our human belief that reality is whatever the scale says it is.

Gödel Walks Into the Kitchen

Penrose tells a story about sitting in a mathematical logic class in Cambridge and learning Gödel’s incompleteness theorems properly for the first time. It hit him like a thunderclap — and it’s easy to see why.

Gödel proved that any formal system powerful enough to do arithmetic will always contain truths it cannot prove — even though those truths are, in fact, true.

A mathematical Kitchen Scale, if you like.

Even worse:

No system can prove its own consistency from within itself.

If it tries, it collapses into contradiction or circularity.

So the system — the scale — is always limited.

It cannot see everything that is true.

It cannot certify its own reliability.

It cannot step outside itself.

But we can.

The Missing Gödel Expansion

Gödel didn’t just show that systems have unprovable truths.

He showed something stranger, almost impolite:

A system cannot fully describe itself.

Not in mathematics.

Not in physics.

Not in consciousness.

Not anywhere.

A Kitchen Scale can weigh everything except the hand holding it.

This was the subtle piece missing:

Gödel exposed a kind of built-in blindness in all closed systems.

If a system tries to explain itself from within, it:

loops

contradicts itself

or leaves something vital out

It has to. That’s the cost of being a system.

This means:

physics can’t explain why physics works

logic can’t explain why logic makes sense

neurones can’t explain why awareness feels like anything

measurement can’t measure the measurer

Gödel’s incompleteness isn’t a glitch.

It’s the universe whispering:

“You’re more than your instruments.”

Penrose and the Leap Outside the System

This is the point Penrose clings to.

Human understanding can see the truth of a Gödel sentence from outside the formal system.

And that “seeing”:

is not computable

is not rule-bound

is not algorithmic

is not measurable

This is Penrose’s controversial leap:

consciousness isn’t acting like a formal system at all.

It behaves more like a non-computable insight engine — something that grasps truth directly, not through calculation.

Just as our experience grasps realities the Kitchen Scale cannot weigh, or the Sieve cannot separate.

Gödel, the mathematician, quietly supports the Teaspoon, the Whisk, and the Sieve.

Penrose, the physicist, looks at Gödel and concludes:

something about consciousness isn’t captured by the rules.

Measurement, Mis-measurement, and the Human Blind Spot

We humans adore certainty.

We adore numbers.

We adore the scale because it gives us a sense of control:

200 grams of flour

3 teaspoons of sugar

Proof. Precision. Certainty.

But certainty is a comfort, not a truth.

Awareness doesn’t weigh in grams.

Meaning doesn’t appear on a dial.

Yet we trust the scale more than we trust the thing doing the weighing — ourselves.

That’s the absurdity Gödel points to, Penrose worries over, and the Cosmic Kitchen illustrates:

We built a measurement system

that cannot measure the one thing

we’re absolutely certain is real —

our own awareness.

Summary

The Kitchen Scale isn’t wrong.

It’s just inadequate.

And the trouble starts only when we mistake adequacy for authority.

The Whisk, the Sieve, and the Teaspoon aren’t tools we invented.

They’re behaviours baked into reality long before human beings appeared:

turbulence forming meaning

filtration forming structure

awareness sampling experience

Measurement comes afterwards — the latecomer at the party.

Gödel’s great gift was to show us that no system can contain the whole of itself.

The Kitchen Scale weighs ingredients, not experience.

Formal logic proves theorems, not meaning.

Physics predicts motion, not awareness.

The one thing capable of stepping outside the system

is the thing doing the stepping:

Reality isn’t what fits onto the scale.

Reality is what notices the scale is even there.